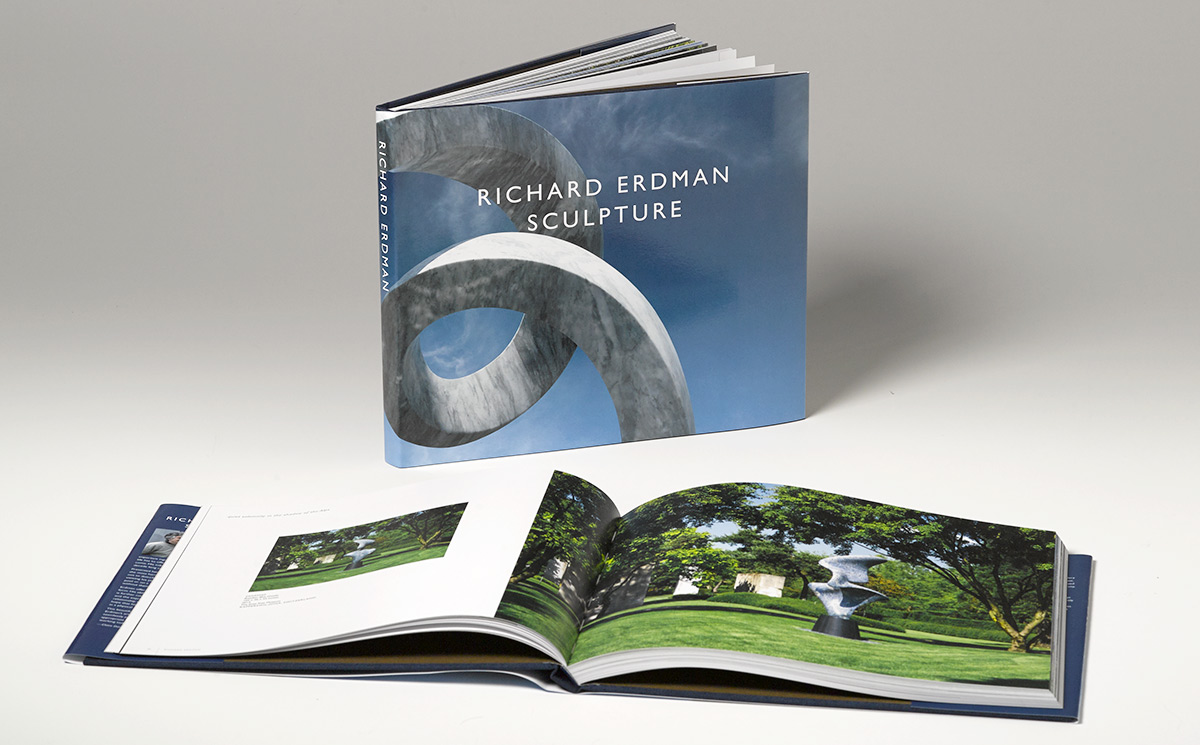

Announcing Richard Erdman’s new Monograph

July 24, 2017

Richard Erdman is excited to announce the release of his new monograph, Richard Erdman Sculpture. The monograph is a survey of monumental works in stone and bronze created in the last decade and includes 158 color reproductions. With essays by Amy Rahn and Michael Wehunt, this 160-page hardcover book takes the viewer on a journey around the world, to the vast and harmonious environments in which Erdman’s sculptures are placed: upon shimmering water, among ancient trees near Lake Zurich, a bucolic English estate, and a bustling corporate lobby in New Delhi. The prominent presence of each sculpture does not impose upon the landscape, but rather enhances it, grounding the surrounding communities and creating an environment of beauty and contemplation. Below is Amy Rahn’s, Perpetual Sublime, an essay featured in Richard Erdman Sculpture.

Richard Erdman’s Perpetual Sublime

Amy Rahn

“As children, Richard Erdman and his siblings swam in quarry basins hemmed by vast gray-white faces of marble. The glassy water revealed the patterns of the marble’s ancient making—millennia of prehistoric sea creatures, their shells emptied, sedimented and compressed over millions of years into stone. For Erdman, it was a glimpse through time. “I was a diver in another world.”

Cut away by a century of labor, the quarry cliffs and basins were playground and kingdom to the Erdmans, whose days were spent exploring the countryside around their home in Dorset, Vermont. On Sundays, Erdman and his friends would sneak into the nearby Danby quarry, the world’s largest underground marble quarry. The hundred-year-old quarry is one and a half miles deep, and almost a hundred feet high at its most cavernous. Creeping along its catwalks, the boys turned on the work lights, exposing, in a great wash of industrial light, sheer imposing cliffs—a silent amphitheater of vertical stone. Amid the towering walls, Erdman called it “Hall of the Mountain King.” The immense scale of the space and its compression of ancient time connected Erdman to the continuity of life; he felt himself in the presence of the divine. With stone, reluctant material and enduring record, ground and sanctuary, Erdman was fully aware, fully awake—alive in the world. Stone ignited Erdman’s craving for a heightened experience of being alive, a quest that has fueled his four decades as a sculptor. It is to this expansive edge of human experience that he seeks, as an artist, to bring his viewers.

As a teenager, Erdman found peak experience in professional skiing, cutting bright curves in the glimmering mountain snow, riding the mountain’s pitch. Gravity pulled his legs and cold air burned his cheeks as he sailed downhill at breathtaking speeds, feeling the immensity and immediacy of the natural world.

As a college student at the University of Vermont, Erdman found a lifelong mentor in artist-teacher Paul Aschenbach, who encouraged Erdman’s adventurous spirit by emboldening him to experiment with tools and materials, unfettered by the techniques of sculptural tradition. The athleticism and passion Erdman brought to the mountain he now applied to his labors in the studio, spending countless hours hewing stone into his nascent vision. Under Aschenbach’s mentorship, Erdman translated his search for the outer boundaries of embodied human experience into a search for visual forms capable of expressing such experience, and of catalyzing it in others.

Early works like his 1976 piece Broken Promise blend roughly textured and smoothly contoured surfaces in the tradition of sculptor Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), who, like Erdman, worked in both stone and bronze. In both sculptors’ stone works, the contrast of rough stone with finely finished figurative forms evokes the emotional state of the figure. In Erdman’s Broken Promise, the figure is compressed, almost cubic. The figure’s knees draw up as his arms press, one elbow akimbo, to his head. In place of the torso, rough marks pile into a columnar shape, holding the figure static, encased. The smooth articulation of the figure subsumed by the sculptor’s chisel marks seems a representation of both figure and sculptor; the figure struggles to emerge and the sculptor labors to free him. The moment of struggle is suspended, elongated indefinitely. Erdman’s handling of stone makes the figure’s surging suffering available to the emotional experience of the viewer—not just understandable, but perpetually occurring.

In Erdman’s works of the 1980s and 90s, including his landmark work Passage of 1983-85 , his works became less directly figurative, and more concerned with the expressive possibilities of purely abstract forms. Passage marked not only Erdman’s entrée into monumental scale, (it is still the largest sculpture ever to be carved from a single block of Travertine marble)[1], but his virtuosic blending of figurative suggestion with a complexly conceived orchestration of three-dimensional abstract forms. As art critic Peter Frank wrote, “Passage’s […] most remarkable moment—its formal hat trick and climactic display—is the sense that the sculpture is climbing in on itself.”[2] The effect of the work, as experienced in three dimensions, is neither that of the stone’s stillness, (despite the grain of the stone remaining horizontal along the whole form), nor of a figure emerging from stone, (as in Broken Promise), but rather of the stone moving through its environment. It is as though the stone awoke from its millions of years of slumber in the mountain and stepped out into the grassy field. Like the subterranean quarry where Erdman first glimpsed the world’s ancient memory, Passage is a site of renewal, where the viewer’s presence summons forth the continuity of past and present.

In Erdman’s works after Passage, surface and form often open, swirl and fold with the supple organic elegance of splashing water or curling waves. In the tight coils of Sonnet, the wide planes and simplified form of Continuum, and the expansive gesture of Helio, Erdman pressured stone and bronze, refining, polishing, and blending forms in an ongoing quest to distill an essence of euphoric revelation, to still it, to share it.

Continuum 1/3, Bronze

In his recent works, Erdman evokes unbounded experience by constructing forms that hold space without containing it. His forms are open and flowing, yet rooted; they gather and release the space around them, like a momentary revelation that occurs in a string of ordinary moments. In his 2014 work Eleos Cascada , looping bands of gray-white marble swoop upward, seeming to coil and then loosen with the viewer’s movement. The entwined ouroboroi feed back into themselves in a ceaseless loop, twisting and rolling as though possessed of muscle and will. Across the sculpture’s surface, striations of gray and white cut laterally and vertically along its long curves, the grain of the stone crisscrossing and unfurling around itself, echoing and upending the ancient sedimentary processes that originally formed the stone. In its installation in Cabo San Lucas, Mexico, Eleos Cascada hovers, almost miraculously, over a rectangular pool of clear water. The Pacific Ocean beyond, the placid water beneath, and the gray-white veined stone above join the brilliant blue horizon in a symphony of linked patterns. The work, poised over water as it was before carved— a block of stone high in a quarry wall—here joins earth, sky, and sea. At the intersection of human and monumental scales, human lifetimes and geologic epochs, the work connects viewers to elemental forces and its surroundings, offering a heightened encounter with the present.

Eleos Cascada, Bardiglio marble

Erdman’s quest to create works that carry the possibility of revelation has resulted in some thousand works in stone and bronze, a testament to Erdman’s work ethic and focused vision over his forty-year career. While his work resides in impressive collections worldwide, it is the work itself that is the lasting mark of Erdman’s career. “Stone is the material we love to leave,” Erdman says; he labors under the knowledge that a sculptor can make only a limited number of works in his or her lifetime. The arduous nature of the work makes acute demands on the body, thus even with trusted assistants, a stone and bronze sculptor’s body of work depends on his or her able body. The sculptor, as he works, marks his own passage of life in sculptures that will long outlast all who now see them.

It could be said that mortality is the bound spring inside Erdman’s works; they carry the urgency of each moment lived as if it were the last. Fueled by his threshold experiences of nature, Erdman endeavors to wring the fullness from each lived moment, and from each form. He shows us our own present, magnified and expanded like air caught in his sculptures’ stony sinew.

Erdman’s works allow a view of the present, and of ourselves in it, as we might be seen from the quarry’s wall—small figures alive on the edge of vast space and time. Culling stone from the mountain, drawing its sedimented history into long arcs, Erdman does not just show us the glimpse of past and future he saw as a child—earth’s memory locked in stone—he walks us to the edge of ourselves, and turns on the lights.”

Works Cited

Frank, Peter, ed. Richard Erdman: Skylark Press, 2008.

Richard Erdman, Amy Rahn. “Interview with Richard Erdman.” Unpublished, 2015.

[1] The block weighed 400 tons when quarried. Passage may be the largest freestanding sculpture ever carved from a single block of any kind of marble. Peter Frank, ed. Richard Erdman (Skylark Press, 2008). 108.

[2] Ibid. 115-116.