The sculpture of Richard Erdman is entwined with the history of marble and the source of the most renowned marble in the world: Carrara, Italy. Having maintained a studio in Carrara for decades, Richard’s work is imbued with the region’s rich legacy of stone, from Michaelangelo to the newest generations of marmisti in training. Richard deeply values his place in Carrara’s long lineage of artists and stoneworkers, and takes pride in his studio’s role in ensuring the health of Carrara’s marble-working artisanry for generations to come. Read on to learn more about Richard’s practice and the story of Carrara marble, from ancient times to the present day.

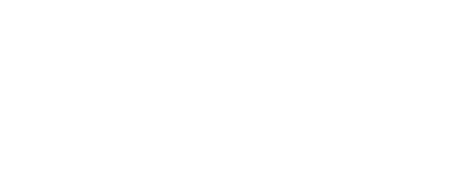

Carrara, Italy, general view near the head of the valley, 1913

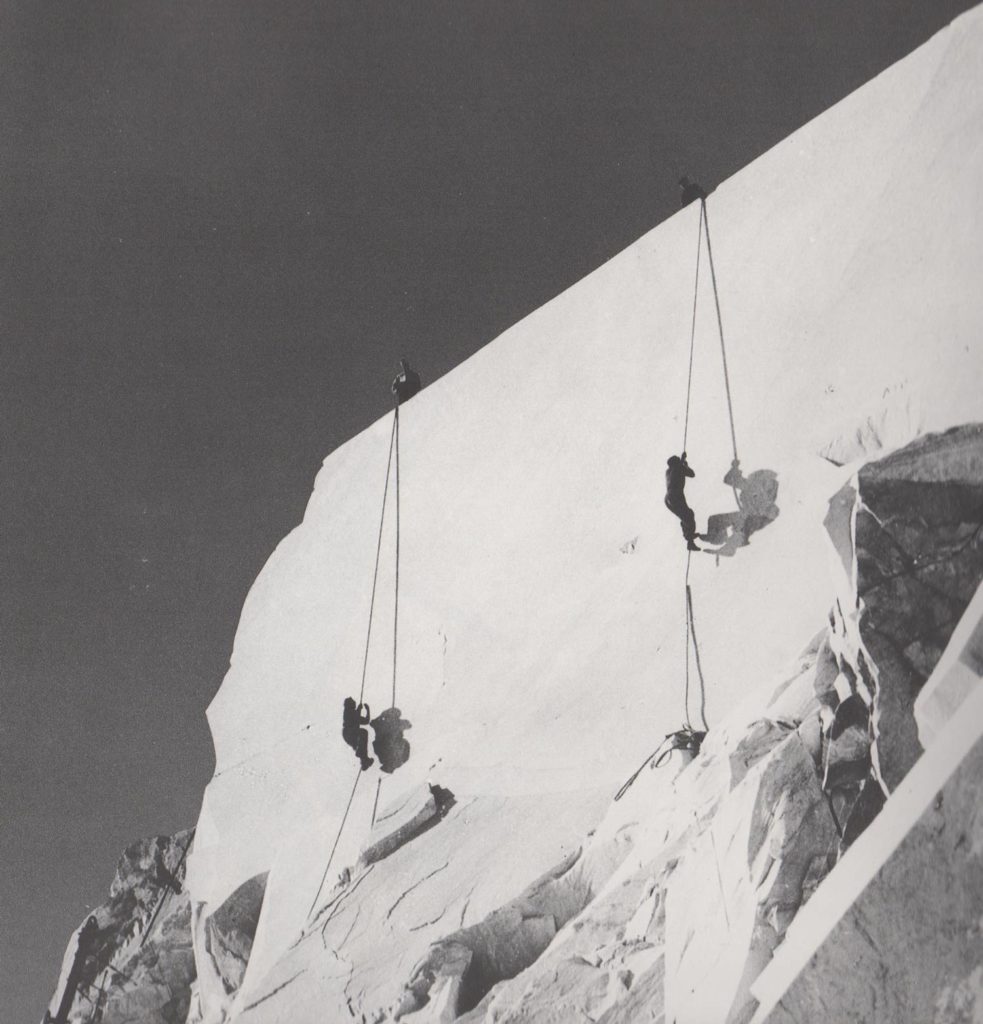

In the 1800s, when mine blasting, known as varate, was used to extract large pieces of marble from the mountain, a tuba was played, emitting very low notes, to warn of danger.

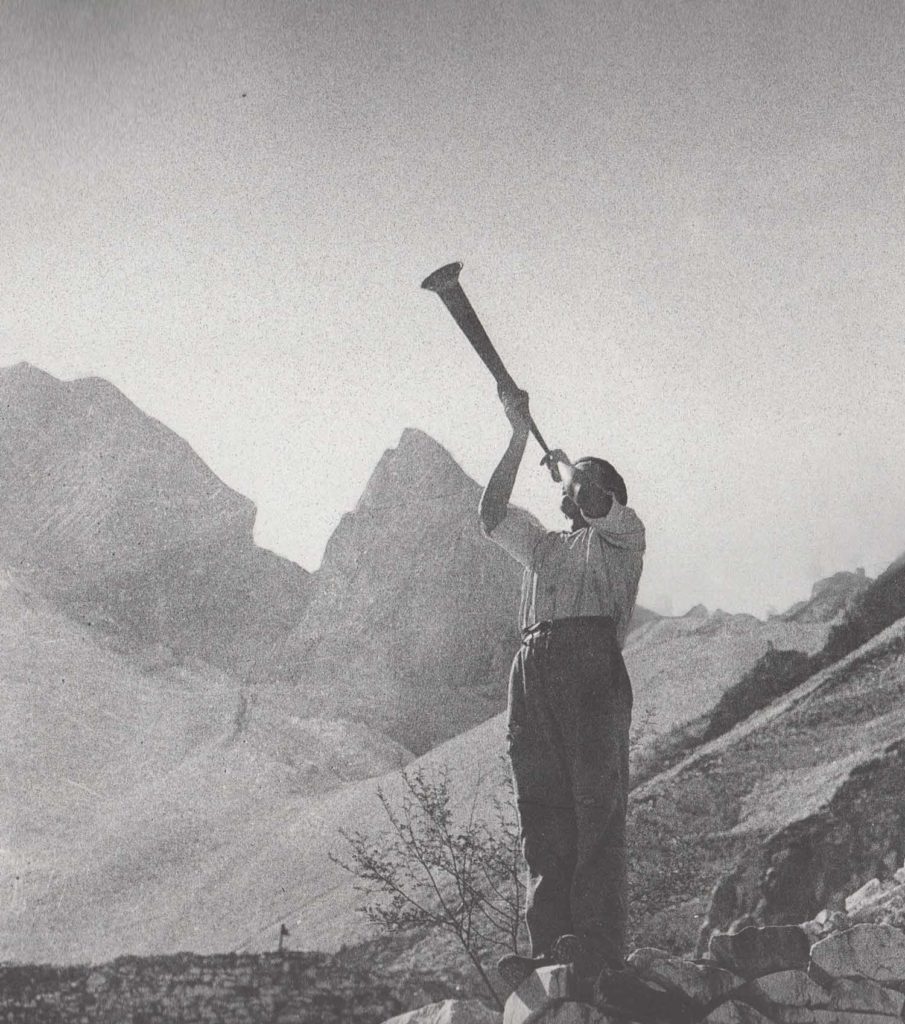

Otherworldly glow of the quarry interior

Isamu Noguchi in Carrara, Italy, 1953

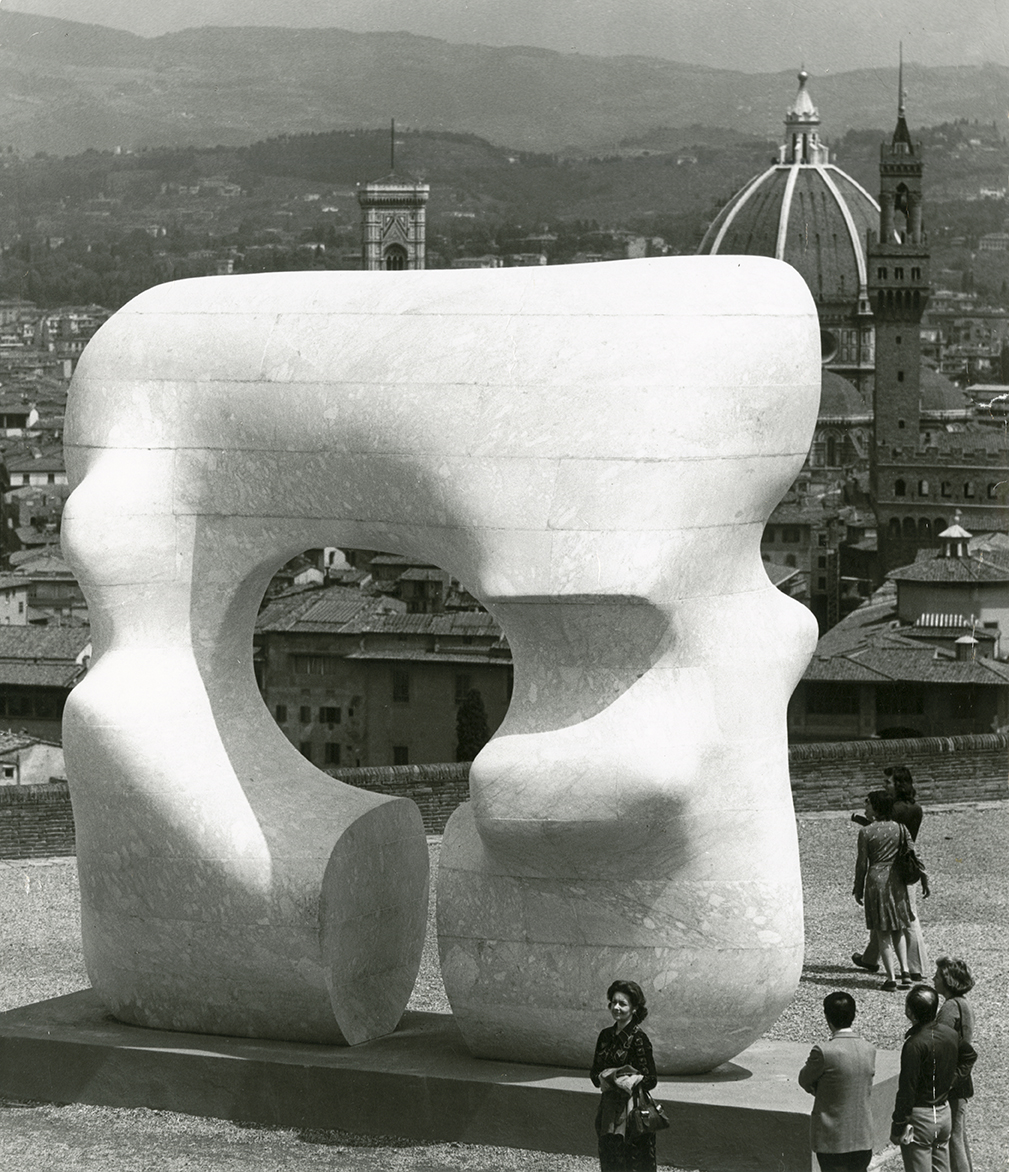

Henry Moore, Square form with cut. Florence, Italy, 1972

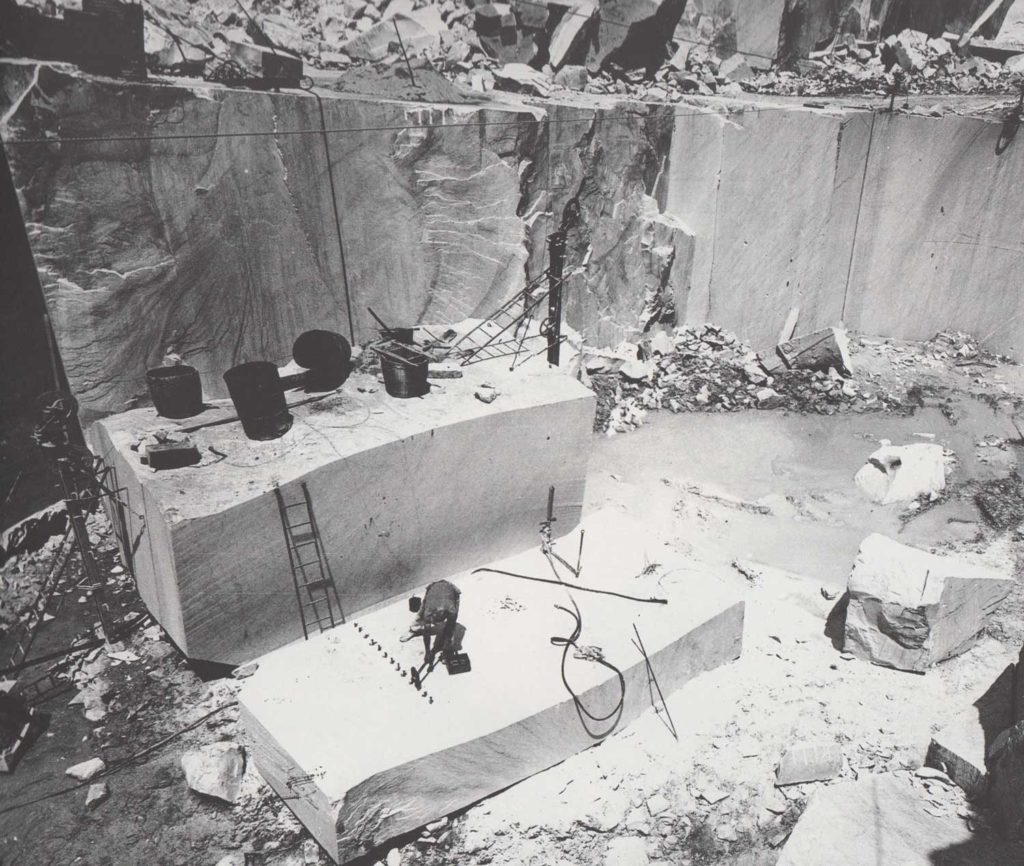

Working in the quarry

Ascending

Marble wagons pulled by Oxen, 1913

The quarries near the head of the valley, 1913

Carrara History

Poised at the foothills of Tuscany’s Apuan Alps, Carrara and the surrounding region is recognized as the birthplace of some of history’s most celebrated sculptures. Decades after Richard’s first pilgrimage to the heartland of marble, both he and his work have become part of a rich and storied lineage shaped and shared by generations of artists — Michelangelo and revered modern figures Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, and Isamu Noguchi among them. By choosing to work in Carrara with marble as their medium, each of these artists chose not only to connect with stone, but to enter into collaboration with place, tradition, and the skilled marmisti who have kept that tradition alive for centuries.

Geologic Time, Ancient Discovery

I found Rome a city of bricks and left it a city of marble.” – Emperor Augustus

First discovered and prized by the Romans more than 2,000 years ago, Carrara marble was born from transformations that must be measured on a geologic time scale. When tectonic plates collided beneath the Mediterranean coast 50 million years ago, nearly unfathomable heat and pressure compressed deposits of oceanic limestone, spurring the material’s metamorphosis into marble. That limestone was made from the calcium carbonate of early organisms, and it is not an exaggeration to say that Carrara marble is made from ancient life forms.

The Romans first uncovered marble in the town they named Luna. That site is the present-day village of Luni, less than 10 kilometers from the source of the marble used in Richard’s sculptures. Recognizing the material’s inimitability, the Romans used it to build many of their most celebrated monuments, including the Pantheon, Trajan’s Column, and Portico di Ottavia, forever solidifying Carrara marble as foundational to the history of civilization.

In the centuries to follow, the reverence for oro bianco – white gold – only grew as it became a coveted material for Renaissance sculptors. Michelangelo himself traveled to Carrara for periods of four to five months in search of the exact stone he would use for his works; both the David and Pietà are rendered in the purest white statuario Carrara marble.

Modernism in Marble

It was one of Richard’s primary influences, Henry Moore, who led the cadre of post-war artists to Carrara marble. Moore first traveled to Pietrasanta, just west of Carrara, in 1957 to work on his Reclining Figure for the UNESCO headquarters housed in Paris. Promptly falling in love with the area, he purchased a home in the nearby Forte dei Marmi. “I was like a little child seeing the window of a sweet shop,” Moore said upon his first time seeing the Apuan quarries that tower above the villages below.

At Moore’s encouragement, many other celebrated artists trekked to the marble capital, including Jean Arp, Joan Miró, and Isamu Noguchi. Colombian artist Fernando Botero bought a home in Pietrasanta in the early 1980s, and today his presence is kept alive through two frescoes inside the town’s Church of the Misericordia.

An Evolving Lineage

Painting is a solo song. Sculpture is a chorus.” – Gustavo Aceves

Nestled alongside a winding road just north of Carrara’s city center is the studio where Richard’s sculptures are born. The Studio, SGF Scultura, was founded in 1971 by Mario Fruendi and partners Silvio Santini and Paolo Grassi. All three men were born in Carrara and studied together at the Carrara Accademia dei Belli Arti.

As young men just beginning to establish their careers, Richard and Mario struck up a friendship that would become a lifelong partnership of collaboration in stone. Richard first met Mario in 1979, during his early visits to Carrara. In 1983, Richard was commissioned to create a monumental work for the Donald M. Kendall Sculpture Gardens at PepsiCo. Passage became one of the world’s largest sculptures created from a single block of stone. Guided by Richard’s vision, Richard and colleagues worked together from start to finish, bringing Passage into being and solidifying their formidable partnership.

As inheritors of Carrara’s history, Mario and his family of stoneworkers stand as a vital link between the tradition’s past, present, and future. In the 19th century, a new level of industry brought an influx of workers to the region. Laborers were hired to cut and extract stone, and to drive sleds as well as carts moved with trains of oxen. While some outmoded practices (such as oxen) have certainly been updated, Carrara’s artisan stoneworkers continue to use hand tools and techniques passed through generations. Callipers and compasses are still used to scale out a new work, moving between a model and a yet-uncarved block of stone.

Today, the Italian studio is family-run with Mario’s wife Luisa managing its offices. With a highly-skilled team of artisan stone cutters, carvers, and finishers and a constant flow of projects, the workshop both employs stoneworkers and trains young apprentices to bring the tradition into the future. Richard finds no greater joy than working between his homes in Vermont and Italy, bringing his works to life with the support of a team that he considers family.

Timeless Form

From his first voyage to Italy to his most recent glass of wine with Mario, Richard knows that the spirit of Carrara is in his bones and infuses his sculpture. Fueled by reverence for centuries of tradition and the thrill of unknown futures, Richard works at the meeting point of land and history with an awe that never subsides – it is that awe that he seeks to elevate in his timeless forms.

Essay by Rachel Elizabeth Jones